[ad_1]

At least eight people have been diagnosed with measles in an outbreak that started last month in the Philadelphia area. The most recent two cases were confirmed on Monday.

The outbreak began after a child who’d recently spent time in another country was admitted to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) with an infection, which was subsequently identified as measles. The Philadelphia Department of Public Health considers the case to be “imported” but did not say from where.

The disease then spread to three other people at CHOP, two of whom were already hospitalized there for other reasons.

Two of those infected at the hospital were a parent and child. The child had not been vaccinated and the parent was offered medication usually given to unvaccinated people that can prevent infection after exposure to measles, but refused it, the Philadelphia Inquirer first reported.

Despite quarantine instructions, the child was sent to day care on Dec. 20 and 21, the health department said.

At that day care facility, called Multicultural Education Station, four more people got infected. A day care staff member said its administrator was unavailable for comment.

Health officials in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, warned on Thursday that a person with measles visited two healthcare facilities there on Jan. 3, which in turn exposed others. No cases have been confirmed in the county, however.

None of the people in Philadelphia who’ve been diagnosed was immune to measles, the city’s health department said, which means they either never got a measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine or had not contracted measles in the past. The health department declined to offer specifics about the patients’ ages or vaccination status, however.

The outbreak has led four people to be admitted to the hospital in addition to the two who were already hospitalized, the department said.

Philadelphia hospitals are on high alert for new cases, since measles is very contagious. An infected person can infect up to 90% of the people close to them if those contacts aren’t immune. People can remain contagious for roughly eight days (four days before the disease’s signature rash appears and four days after).

The virus can also survive up to two hours in the air after an infected person leaves an area.

“With those who’ve had a rash, certainly we’ve been on the highest alert, but we are asking everybody about exposures to people with measles,” said Dr. Doug Thompson, chief medical officer at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children in Philadelphia.

Thompson said the hospital has seen three measles patients in the current outbreak — all between 1 and 2 years old. None had been vaccinated, he added.

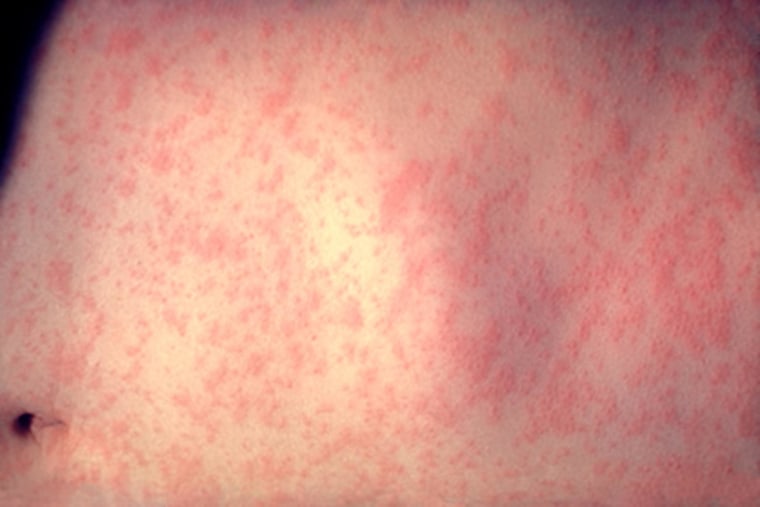

Measles usually causes a high fever, cough, runny nose and red, watery eyes. Then a red, blotchy rash may form three to five days later.

Roughly 1 in 5 unvaccinated people who gets measles is hospitalized, and 1 to 3 out of every 1,000 children with measles dies from severe complications such as pneumonia or swelling of the brain.

People who’ve been vaccinated and get exposed shouldn’t worry about getting sick, Thompson said. One dose is 93% effective at preventing measles, and two doses are 97% effective, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The protection is lifelong.

At least 93% of children in Philadelphia have been fully vaccinated against measles by age 6. Children get their first dose between 12 and 15 months and their second between 4 and 6 years old.

For people who get exposed and aren’t immune, a vaccine can still ward off infection if administered within 72 hours. Another option is a preventative injection called immune globulin, which delivers antibodies. It must be given within six days of exposure.

Thompson estimated that more than 15 people who may have been exposed to measles at St. Christopher’s have received immune globulin.

“If somebody was at the hospital sitting in the same room with that patient — in the waiting room, let’s say — and they were deemed at risk, we brought them into our emergency department and we gave them the immune globulin,” he said.

A smaller number of people exposed at the hospital received a measles vaccine, Thompson said.

The U.S. effectively eliminated measles in 2000, though there are occasional outbreaks that originate in other countries.

From October to December 2022, the CDC confirmed 85 cases of locally acquired measles in Ohio. Earlier that year, four Ohio residents had brought measles to the U.S. after traveling to East Africa, but the CDC could not definitively link the outbreak to those cases.

New York experienced a large outbreak in 2018 and 2019 that began when unvaccinated travelers returned to the U.S. from Israel. The CDC confirmed 242 cases in the state, excluding New York City, from October 2018 to April 2019, as well as 33 cases in New Jersey.

Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said the recent outbreaks are likely a result of declining vaccination rates.

“Measles is the most contagious of the vaccine-preventable diseases, so when you lower immunization rates, that’s the first disease to come back,” he said.

For nearly 10 years, the share of U.S. kindergartners who had received two doses of the MMR vaccine was 95%. But that rate fell to 93% in the 2022–23 school year. The number of people claiming vaccine exemptions for their kids has risen in the last year.

Offit pointed to misinformation about vaccine safety, opposition to vaccination requirements and parents’ fears about taking their kids to the doctor during the Covid pandemic as factors that have driven the trend.

People also seem to have forgotten how contagious measles can be, he said.

“People falsely think that you’re only going to get measles if you come in direct contact with somebody who has measles. That’s not true,” Offit said. “It’s these very fine, aerosolized droplets which contain measles that hang in the air like a ghost. And until they settle, you’re at risk.”

[ad_2]

Source link